Side by Side: Traveling the Road and Sharing the Load of Alzheimer’s Disease

It was November 1996. My husband and I were enjoying a concert of the Pittsburgh Pops. Two performers came on stage dressed as hobos with smudged faces, soiled baggy pants with patches, torn and tattered shirts, and sacks carried at the end of a stick. Their “shtick” was a song-and-dance routine. As they sang “Side by Side,” tears ran down my cheeks and I muffled a small sob. I knew what was ahead for my husband, Dave, who had been newly diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). I knew that, as his caregiver, we would “travel the road, sharing our load, side by side.”

And so we have.

Pre-Diagnostic Observations

Dave, who celebrated his 59th birthday on March 23, was formally diagnosed with AD almost five years ago. However, I began to notice subtle personality changes as early as age 48. By 50, Dave began to have difficulty remaining on target during a conversation. This escalated over the next two years as I noted that Dave’s participation in social conversation was almost absent. In 1994 – two years before his diagnosis – he began to exhibit word-finding deficits and relied on circumlocution during expressive attempts. He also began using stalling mechanisms such as coughing and saying “excuse me” or “just a minute,” during brief telephone encounters. The following year, he developed a facial tick that later was diagnosed as oral-mandibular dyskinesia.

During his professional career, Dave had been an attorney with Mellon Bank. He had a very high degree of responsibility within the bank and I watched as his work productivity eroded until he could no longer process the complex language of legal briefs, prepare for meetings, or manage household finances.

In June 1996, Dave and I traveled to Boston where we rented a car and hit the road to New Hampshire to visit my sister. With dismay and increasing fear I noted the difficulty Dave had following a map, a skill I never had but one at which Dave had been proficient. When we returned from Boston, I made an appointment for Dave to be examined by a neurologist. An MRI was ordered immediately and completed without evidence of focal lesion or tumor. After a series of additional “rule-out” medical examinations, including extensive lab work and a thorough neuropsychological evaluation, it was determined that the diagnosis was probable early onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Dave retired immediately from the bank.

In writing this article I do not attempt to review the literature, which is exhaustive, nor can I share with readers the many techniques I devised to maintain Dave’s functional abilities as they declined over time. My intent is to:

- provide a description of the disease progression over a five-year time frame, with the unique and ironic advantage of both the personal and clinical perspectives

- discuss the linguistic deficits experienced by my husband

- explain a functional meaningful communication intervention designed to allow Dave to communicate at an adult level

- review Medicare coverage guidelines for Skilled Maintenance Programs (SMP)

Dave’s Disease Progression

For the first four years post-diagnosis, Dave’s disorder was primarily one of information processing. With each year his ability to decode and encode information declined significantly. The ability to use the language of mathematics was gone within the first year. Thus, he was unable to write checks, use money, or understand household finances. Dave was still able to communicate within a conversational setting, but required assistance when experiencing word-finding difficulties. When watching television, he would mute the audio, preferring to rely on closed captioning. He also enjoyed foreign films with subtitles and the opera with its libretto. This preference for the written modality is consistent with the research findings of Michelle Bourgeois, whose early work on the development and use of memory wallets for individuals with AD demonstrated that the preservation of written language is retained far longer than any other language modality.

During years two and three, Dave’s ability to process verbal communication declined significantly. There was an increase in the breakdown of expressive language. He could no longer write or copy, his word-finding deficits escalated, and echolalia was present and seemingly used as a turn-taking pragmatic. Dave also began to experience perseveration of thought and action.

In analyzing Dave’s linguistic errors I went back to my early training as a speech-language pathologist (SLP), to the teachings of Hildred Schuell, James Jenkins, and Edward Jimenez-Pabon, Aphasia in Adults, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment (Hober Medical Division, Harper & Row, 1964). As an undergraduate, I was taught then and continue to adhere to the findings of Schuell, et al., that “the language behavior of aphasic patients, bizarre as individual responses sometimes appeared, was predictable and orderly and related to general laws governing language behavior.”

I still find value in the linguistic view of aphasia as described in the early writings of Jackson and Hale in Fundamentals of Language (1956). Jackson and Hale felt that language at all levels consists of two general and largely independent processes, selection and sequencing. In applying Jackson and Hale’s view of the disorder I have been able to categorize the aphasic language of my clients within the linguistic divisions of phonology, morphology, semantics, and syntax.

Thus, as I listened to Dave’s spoken language, I recognized selection disorders at the phonological level-for example, the intrusion of (î) within the words of goodbye and okay with the resulting output of “goodblye” and “oklay.” I noted selection problems at the semantic level with word substitutions like table for chair or cat for dog. Dave had sequencing disorders at the phonemic level that were particularly challenging since it required a quick unscrambling by the listener to recognize a real word instead of assuming a neologism. For instance, “tubon” for button. Often Dave’s language was a combination of disordered linguistic elements such as “tubonmyloat,” which translated as “button my coat.” The success of such translations requires the listener to be sensitive to contextual and environmental cues.

By year four Dave began to experience additional information processing problems. He had intermittent difficulty understanding how to use everyday objects, using the tablecloth as a napkin, having difficulty sitting down in a chair -the beginnings of visual agnosia and motor apraxia. Language had further eroded with the development of oral apraxia and true neologisms.

In addition to the continued difficulties in information processing, year five ushered in the “three fates”-depression, anxiety, and agitation. These psychological disorders became the second major presenting problem. For payment purposes, SLPs working on a cognitive/communicative program should use the cognitive CPT code while a psychiatrist treating the psychological aspects of the disease would use the psychiatrist’s visit code.

The psychological aspects of the disease had a direct impact on Dave’s ability to process verbal language. When the psych disorders became the greater of the presenting problems, Dave’s ability to process language or his environment was nonexistent. Only through the application of polypharmacy was his physician able to reduce or eliminate the wandering, crying, jargon, and repetitive behaviors-the outward manifestations of Dave’s internal psych disorders. Thus, with appropriate medication, Dave is able to continue to communicate using a combination of words, gestures, spontaneous phrases, and the newspaper.

Gail Neustadt helped her husband Dave to read by capsulizing messages into short phrases, using chunking for long phrases. To increase the probability of Dave’s success, she experimented with font style, figure ground, and size of type.

A Functional Intervention

Based upon my years of listening to speech and language, I have concluded that effective conversation is not predictable. It meanders, going from topic to topic and containing an element of surprise. While normal speakers are able to exchange facts and ideas, solicit information, and convey emotion during conversation, individuals with language processing disorders require assistance in varying degrees.

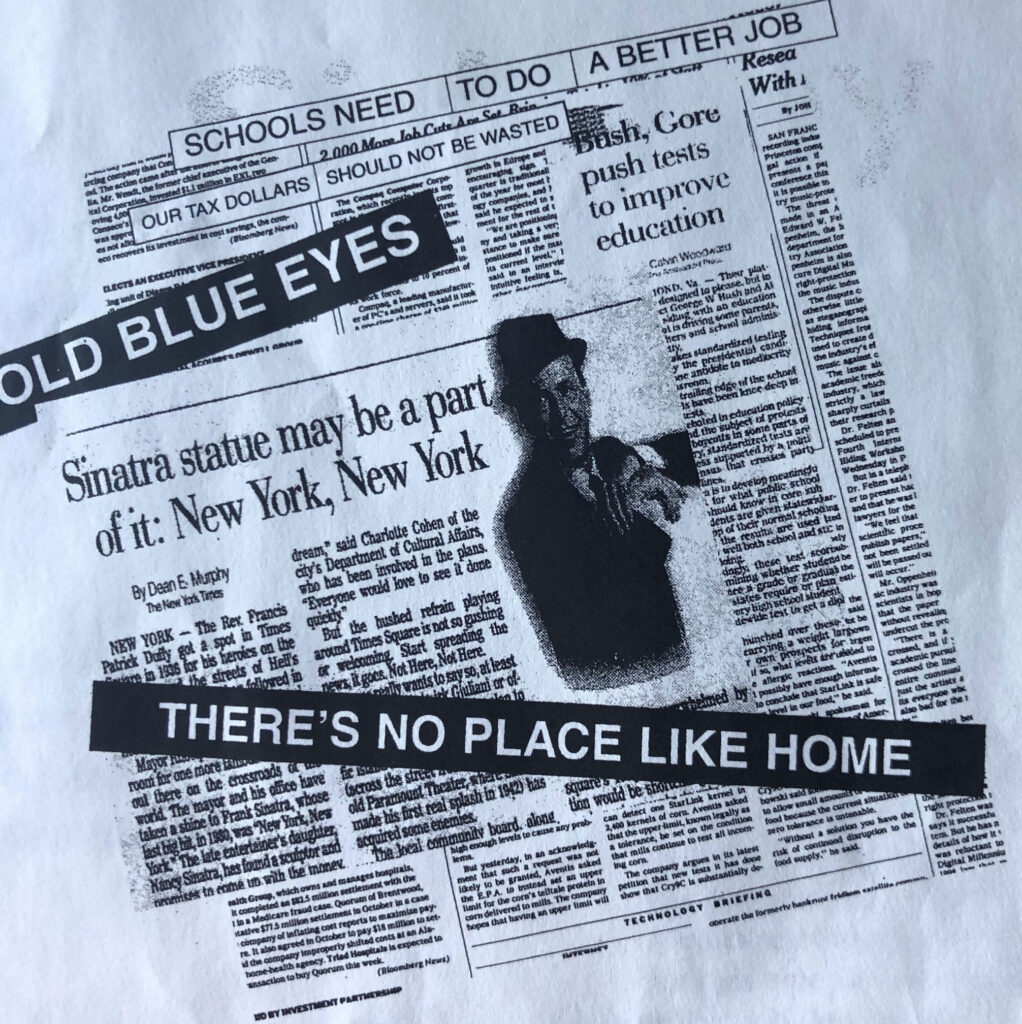

Three years post-diagnosis, I began to use the newspaper in a therapeutic manner with Dave. As a practicing SLP, I always used client-centered interventions. Dave had been an avid reader of several newspapers and periodicals all his life. It was an obvious selection and one to which we could both relate.

At first Dave selected articles he wanted me to read with him. He would read aloud and I would provide assistance when he had difficulty with a particular word. I was able to ask yes-no questions as well as steer the conversation when an article would trigger a remembrance. This activity allowed Dave the independence of selecting the topic, permitted non-directive practice in oral reading, created an element of surprise, and gave Dave the opportunity to engage in adult social conversation that became the focus of our after-dinner recreation.

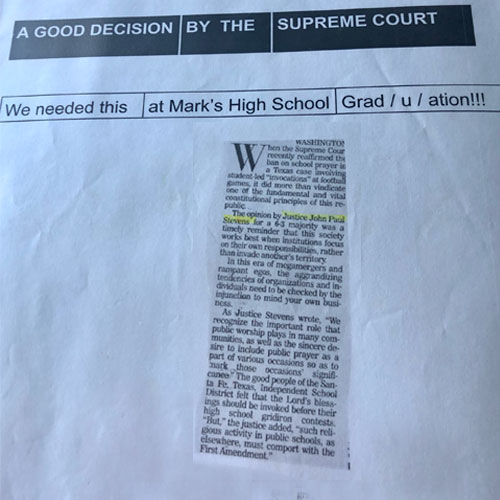

In year four post-diagnosis, Dave’s ability to read aloud was reduced to short phrases. Dave still selected the articles and topics he wanted to share with me. With the help of his caregiver, he cut out pertinent articles and saved them for our after-dinner conversations. Selections included national news, international news, political cartoons, and trivia that he found of interest. In order to stimulate more reading opportunities, allow Dave to say something about the article, and preserve the importance of the effort, we scanned selected articles onto the computer screen and then printed. Scanning allowed the size of the article to be increased, making it easier for Dave to read.

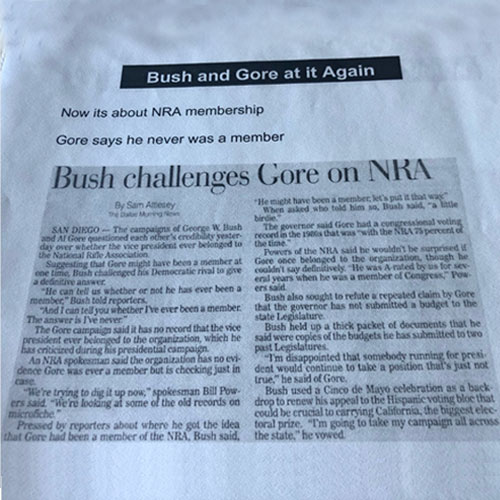

Understanding Dave’s political opinions over the years, I was able to write a three- or four-word phrase that Dave was able to read back, in essence putting words into his mouth. If Dave had difficulty saying a phrase, I would analyze the characteristics of the phonemic construction and syllabification and adjust accordingly until he was successful. For example, instead of “Bush challenges Gore on NRA,” I wrote, “Bush and Gore have a gun fight.” I used chunking when a phrase was too long.

Experimenting with font style, I used figure background and size to increase the probability of Dave’s success (see the illustration above).

Over time, Dave’s ability to read even short, structured phrases deteriorated. We succeeded through the use of idiomatic phrasing like “there’s no place like home” or “where there’s a will there’s a way.”

Once the article was sized, read, and the phrases were selected, the page was printed. All of the “conversational newspaper prompts” have been retained in a three-ring leather portfolio. This allows Dave’s conversations to be both portable and socially acceptable. The briefcase of conversations goes with Dave just as any businessperson might carry a briefcase to work.

Dave’s caregiver encouraged him to embrace the occupational therapy philosophy of work. With her counseling and my reinforcement, Dave soon viewed the newspaper activity as part of his daily work routine, which it always had been. The use of the articles for our evening conversation, although they are adaptations, allows us to carry on a routine, lending a sense of normalcy to Dave’s day and to our relationship.

Carryover of a therapeutic intervention is always a goal of the SLP. However, I was not prepared for the positive instances of carryover that occurred. Once, Dave directed me to an article about the adjustment of property taxes in Allegheny County. He indicated through gesture that I needed to respond. Through a series of yes-no questions Dave communicated that I should call our accountant to discuss the matter. Another instance of carryover was Dave’s willingness to carry his briefcase and share the conversational pages with friends and family. We were invited to dinner at the home of a stockbroker and his wife. Dave cut out an article about the market, placed it in his pocket and at an opportune moment pulled it out and stated, “What do you think of this?” Dave now encourages others to sit down with him and look at the newspaper, using it as a conversational prompt.

When Dave began to spontaneously include pictures of our family in the portfolio, I realized that this was an elaboration of the memory wallet created by Michelle Bourgeois. While most of Bourgeois’ research centered around establishing a communication system for geriatric clients attending adult day centers or residing in assisted living or nursing facility settings, the portfolio was meeting the needs of a community dweller requiring a higher level of communication.

In an article for the Seventh National Alzheimer’s Disease Education Conference (July 1998), Bourgeois discusses “strength-based” programming. “A strength-based program for individuals having cognitive and memory loss is a can-do approach to AD care,” she states. “The intent of strength-based geriatric activities is to provide individuals with ongoing and meaningful therapeutic interventions.” This approach is consistent with the philosophy of functional maintenance discussed in Reimbursable Geriatric Service Delivery, A Functional Maintenance Therapy System (Aspen, 1990) by Glickstein and Neustadt.

Focus on Function

I bought a glass with a red line around the middle. Above the line is the word positive; below the line is the word negative. Dave has his juice out of that glass each morning with some motivational discourse about how “the glass is half full.” Our focus is always on function rather than deficit. Most evaluations are structured to examine disabilities rather than abilities. Bourgeois uses an assessment tool based on the work of Howard Gardner and his theory of “multiple intelligences.” The Informal Geriatric Observation Inventory allows the clinician to evaluate the individual within the context of seven areas of intelligence: verbal/ linguistic, logical/mathematical, visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, musical/rhythmic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. Clinicians are then able to “fuse therapeutic interventions into the living environments and daily routines of the patient with AD.” This is precisely what I accomplished with Dave.

As Alzheimer’s and related dementias are increasing in incidence and prevalence, it is important for SLPs to recognize the possibility of a new target market. Younger individuals still residing within the community who have progressive neurological disorders might benefit from a speech-language consultation. The consultation is a package that should include the initial evaluation, the designing of a skilled maintenance program and any teaching/ training of the program to a caregiver. Medicare covers the cost for this type of consultation if it is properly billed and has realistic and time-limited goals.

Coverage for Skilled Maintenance Programs

A Skilled Maintenance Program (SMP), often referred to as a Functional Maintenance Program (FMP) as identified by Glickstein and Neustadt in Reimbursable Geriatric Service Delivery, is an important part of the service delivery system in long-term care. In nursing facility provider settings, the maintenance program is a skilled and therefore covered service when designed by a qualified physical, occupational, and/or speech-language therapist. Once the program has been established, it is integrated into the facility’s Restorative Nursing Program and becomes a Restorative Maintenance Program (“RMP”). As clinicians in long-term care settings, we are accustomed to writing SMPs. However, such programs are typically not developed for community dwellers. Currently, SLPs are unable to bill directly to Medicare and, in many cases, other insurers. To get reimbursed, the SLP enters into an arrangement/ agreement with a supplier and/or provider who has contracts with the Medicare Program as well as other insurers. The supplier/ provider bills the insurer for the services provided by the SLP and the facility pays the therapist for the service. Although Medicare is a federally funded insurance program for the aged, citizens who are disabled by two or more years are also entitled to coverage. This would include community dwellers with progressive neurological disorders.

Conclusion

Caregivers need someone to “share the load” of Alzheimer’s Disease. An SLP pathologist providing an evaluation, an individualized SMP, and training to caregivers will not only help the client better communicate, but will also lessen caregiver burden. The road of communication has two lanes consisting of the speaker and the listener. Both partners must be able to function at their highest potential. Just as bridges bypass areas that otherwise would not be navigable, adaptations within the communicative environment are necessary to allow the partnership and intimacy afforded by interpersonal communication to continue.

Once the maintenance program is in place, the skilled services of the SLP are no longer needed. However over time the client may experience a functional change. If/when this occurs, the previous maintenance program may no longer be safe or effective. The Medicare program considers the reevaluation and adjustment of a prior program with additional training as needed to be a skilled and, thus covered, service. By maintaining contact with the caregiver, the SLP can support the caregiver and adjust the maintenance program to meet the communicative needs and abilities of the client. (For more on skilled maintenance programs under Medicare, see page 3.)

My personal situation was different, of course, because I was both caregiver and therapist for Dave. It took time for each of us to deal with the situation before we could work together again as a couple and in a therapeutic relationship. Once we were both ready, I could build that bridge of communication with Dave, enriching his ability to communicate and enhancing our relationship.

Like the song says-“Through all kinds of weather, what if the sky should fall, just as long as we’re together, it doesn’t really matter at all.” So far, we have continued on this difficult road, side by side.